The cityofshelters

Catalogue of Barcelona's air raid shelters

Enter

Explore the Map

Searchproposals

-

Domestic shelters

-

Factory shelters

-

Franco's Shelters

-

Shelters of neighbourhood solidarity

-

Shelters of political leaders

-

Shelters with multiple lives

Domestic shelters

One of the districts where most community shelters were built was the Eixample, where the buildings were taller and more robust. Some residents built them openly, with the advice of municipal technicians and with the help of grants. Others did so in secret, without informing their neighbours. This was the case, for example, of the Beltran family. Three neighboring families agreed to build the shelter in complete secrecy, because it was small and could accommodate only a few people. They hid the earth they extracted during the night in carts and hid the rubble under straw so that neighbors would not suspect what they were doing. In 2016, at number 149-151 of Carrer Ausiàs March, the Barcelona Archaeology Service discovered this secret shelter. In red paint, someone had written: ‘Mr. Josep Colomer / built this shelter / in 1937’.

Shelter Torre de la Sagrera. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Latrine in Torre de la Sagrera shelter. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Material in the Torre de la Sagrera shelter. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Shelter in Ausiàs Marc street. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Factory shelters

When the alarms sounded, the workers ran to take refuge in the shelters under the factories. In Sant Andreu, for example, the Sanchís factory had been producing dyes and colourants since the late 19th century. When the Civil War broke out, it was collectivized, given the name Factory Number 11 and placed under the War Industry Committee. The workers made bombs, explosives, detonators, fuses and bullets for Mauser rifles. The shelter must have saved the lives of some workers, because the factory yard was bombed in May and July 1937.

Oliva Artés factory. Author: Encarna Cobo. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Oliva Artés, a highly productive factory producing and repairing machinery, was located on Carrer Pere IV in El Poblenou. The same street housed the headquarters of some social and recreational organizations of the popular classes, such as the Ateneu Colón and the Cooperativa. Like Sanchís, the factory was collectivized during the war and used to produce arms. In its basement there was also a shelter. At that time El Poblenou had one of the largest concentrations of industry on the Mediterranean coast.

Myrurgia’s factory map in 1928, where a shelter was built in 1937.

Franco's Shelters

Franco had a diplomatic, bureaucratic and military alliance with Hitler. There were even Nazi headquarters in the heart of Barcelona. Near Plaça Catalunya were the Banc Alemany Transatlàntic, the German Consulate, the Amigos de Alemania Cultural Association, the German Chamber of Commerce and the German House of Barcelona. Not far away, in the Eixample, was the German Crafts Market, the German Institute of Culture and the German School. When Hitler’s defeat became imminent, Franco changed his discourse radically, and the Nazi banners and symbols gradually disappeared. However, he was not sure that this purge was sufficient and was extremely worried about the advance of Allied troops during World War II: he sent 12,000 men to build a line of bunkers in the Pyrenees (Línea P), and in Barcelona alone he planned 704 shelters.

Plaça de Catalunya de Barcelona. January 1939. Biblioteca Nacional de España

Because the cost of restoring the Republican shelters was very high, the Franco government decreed that shelters for passive defence must be built in new buildings in towns with more than 20,000 inhabitants and that other towns that could be of strategic importance must also have air-raid shelters. However, according to documents of the time, only 22 of the planned 704 shelters were completed. It was a fanciful project because of the high economic cost involved.

Franco’s troops entry in Barcelona. 26th January 1939. Biblioteca Nacional de España

Most of the shelters were concentrated in the center and in the Eixample district, close to the seats of power. One of the theatres that had to make a shelter in its basements was the Teatre Calderón, where the Hotel Calderón currently stands. It opened on 17 February 1945 and closed in 1967. In 1943, a shelter was also built under the Banco Español de Crédito in Plaça Catalunya. In the same year, a shelter was built in the Benet i Campabadal silk ribbon factory, which was active until the 1980s. Many factories in Barcelona shared Franco’s concern and built their own air-raid shelters.

Shelters of neighbourhood solidarity

During the Civil War, a virtual underground city was built in Barcelona, with rules, personal relationships, customs and a coexistence that was marked by the threat of bombs and confinement in a small, dark space. It is estimated that about 1,455 kilometres of underground tunnels were built. One of the shelters that exemplifies the efforts of local communities is that of Can Peguera, which was one of the four neighbourhoods of cases barates (worker’s houses) built in Barcelona during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. The new district was built to house the immigrant workers who were arriving in the city and to relocate the inhabitants of the shanty towns of Montjuïc.

Preparing packages for the front. Barcelona. 28/11/1938. Biblioteca Nacional de España

Can Peguera was a fief of the CNT, and the residents included anarcho-syndicalist leaders and many of the editorial staff of the magazine Solidaridad Obrera. Nearby was the lnstitut Mental de la Santa Creu, one of the most important psychiatric hospitals in Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As it was a major hospital, a huge red cross was visible on it from the air. However, the residents feared that they would be bombed by Italian planes, which flew over the neighbourhood all too often. They did well to build a shelter, because they were indeed bombed.

Community action also allowed this shelter to survive in the period of democracy. In 1998 it was reopened by municipal technicians at the request of the Can Peguera Residents’ Association. Since 2004, visits to the shelter have been organized through the Roquetes-Nou Barris Historical Archive.

Another shelter saved by the local residents was the one under Plaça de la Revolució in the district of Gràcia. It could not be saved in its entirety, but part of it was saved thanks to pressure from local residents and experts in the history of the district. This shelter had also been built by the local community using picks and shovels.

Shelters of political leaders

One of the shelters that can still be visited is in the Palau de les Heures, where Lluís Companys lived during the Civil War. The shelter built under the impressive residence built in the late 19th century by the rich industrialist José Gallart Forgas had a privileged location behind the anti-aircraft battery of Turó de la Rovira. However, this shelter was no secret to the fascists. In fact, they had an aerial photograph of it, and at one point they considered bombing it.

Reception of fighters at the Palau de la Generalitat on 1st May. Biblioteca Nacional de España

Another shelter that has remained unaltered over time is the one under the building that housed the Soviet consulate, on Avinguda Tibidabo. At the entrance, an immense Soviet #plaque# has been preserved, and the interior premises are protected by reinforced concrete. Everything was prepared for a long stay. Near the Palau Reial de Pedralbes, another shelter was built to protect the president of the Spanish Republic, Juan Negrín. On the other hand, nothing remains of the shelter that was built in Casa Milà. The archaeological footprints were erased in 2000 during construction work, and the documents were burned on Franco’s victory for fear of reprisals. The modernist building housed the PSUC offices. It was also the home of one of its political leaders, Joan Comorera, who survived an assassination attempt.

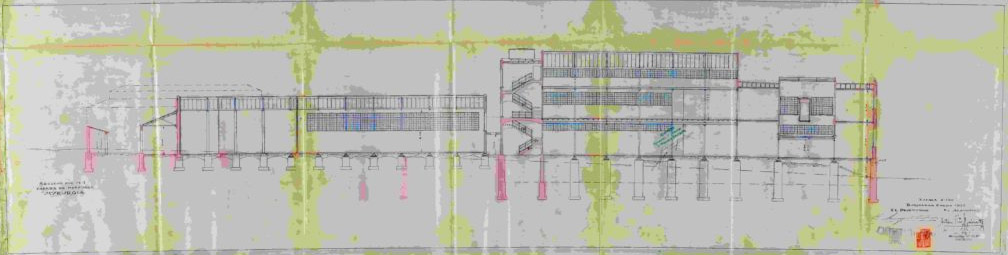

Dossier of the shelter project in Rambla de Catalunya, 33. Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

Shelters with multiple lives

Material in Vila de Madrid shelter. Author: Jordi Pallàs

Shelter 307 on Carrer Nou de la Rambla, one of the few that can still be visited, had many lives: it was used to grow mushrooms, as a glass warehouse and as a shelter for the homeless. The Can Peguera shelter, which was burrowed into the hill called Turó de la Peira, was used as a dwelling by poor families after the war. Some remained living there until Barcelona City Council provided them with decent housing. These are not the only examples of shelters that had a second life as dwellings. Shelters were inhabited for decades because of mass immigration of people from the countryside. In Carrer de Tenerife in the Horta-Guinardó district, a shelter dug into the rock was known as Felipa’s Cave because a woman of that name lived there for years.

Shelter 307 at the time of discovery. 1995. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Shelter 307 at the time of discovery. 1995. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Refugi 307, 2011. Author: Pep Herrero

Sewer in the shelter of the street Juan de Sada. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

- Bombing effects

- Shelter

Map of Barcelona 1935. Barcelona City Council. City Planning Office

Historicalcontext

About the project

The project

For more than fifteen years, the Barcelona Archaeology Service has investigated a key element of the heritage of the Spanish Civil War: air-raid shelters. This website collects all the information, documents, images and testimonies collected during this period, revealing an underground city that was built when the rear became the front and the civilian population was bombed in their homes and in streets, markets and schools.

Through the website, you can browse an interactive map on which more than 1361 air-raid shelters in the city of Barcelona have been geolocated. You can pay a virtual visit to all the shelters, from the first ones built at the beginning of the Civil War in the summer of 1936 to the ones that were built later during the Franco regime.

The objectives

The main objective of this web documentary is to explain who built the shelters and how, when and why they did so. It is intended for all audiences, from experts in the subject to those who are exploring it for the first time. It is a tool for managing and disseminating the heritage of the Spanish Civil War, revealing both the archaeology and the human side of this chapter of our history. We found witnesses to help us explain the construction process, what life was like in the shelters, and how those fleeing from the bombs spent their time and coped with fear and anxiety. We wished to transmit the experiences, the noises and the smells, so that visitors can share the experience of those who lived through that tragic period.

The content

The website is divided into two main sections. The first is the map, where you can search for the shelters by year of construction, district, address or reference number (many of them were registered in 1938 and they are still identified by the numbers used then). The second is the section Shelters today, in which you can see the ones that can be visited, the ones that have been preserved but cannot be visited, and the ones that have been excavated archaeologically. This page links to files containing all the information we currently have about each shelter.

You can make different types of search according to a series of criteria: shelters that were recovered thanks to action by the local community, shelters used for political leaders, shelters in factories, shelters occupied for other uses after the war and shelters that were built during the Franco regime.

It is impossible to understand the shelters without knowing the historical context. Several chapters explain what Barcelona was like during the war, how the population fought the bombs, the solidarity shown to refugees, the destruction caused by the bombing, the fight by the institutions to defend the city, the organization of local communities and the experience of spending nights in the shelters.

The team

This website is the result of teamwork by professionals from a variety of disciplines: archaeologists, historians, communicators, computer technicians and designers. It would not have been possible without the effort and dedication of the many researchers who have preceded us in studying how the Spanish Civil War affected the rear and the civilian population.

Archaeological activity in the shelters

In addition to the knowledge we have from written and graphic sources, nearly forty shelters have been found through preventive archaeology. This type of archaeology depends on the city’s urban planning and construction work and has allowed us to enter some of the anti-aircraft shelters that have been conserved.

When the ground is opened, the first material indication of the existence of a shelter is usually a section of brick wall or of a steeply pitched brick roof.

Although there are always exceptions, most shelters have access at street level via a straight flight of steps, which then makes a ninety degree turn or a double turn and continues with further flights of steps or with the corridors that form part of the shelter. This first section is usually blocked because the Franco government had the shelters filled with rubble to prevent them from being used to hide weapons or people.

The excavation of this first section already offers remnants of the Civil War, because the rubble used was often that of bomb-damaged buildings that had been demolished. When the rubble has been removed, a mortar wall is often found at the first turn. A graphic record of the wall is taken and it is then knocked down. At this moment the archaeologists must be supervised by the Subsurface Unit of the Mossos d’Esquadra (Catalan police), who ensure that the shelter is safe. The safety aspects to be considered include toxic gases, lack of oxygen and the risk of collapse.

When the safety has been ensured, the archaeological work continues. The first task is to clean the interior of the shelter, and then all the elements of the shelter are thoroughly documented, in three stages. First, a survey of the whole structure is made in 2D and sometimes also in 3D. Second, all the materials that were left inside (cans, bottles, clothes, newspapers, personal utensils, etc.) are collected. Finally, the graffiti, plasterwork or paintings that usually cover the walls of the shelters are documented.

This information, together with written documents and the few oral testimonies that remain, allows us to increase our knowledge of the city’s shelters. Finally, a report must be drafted on all the work carried out, including the plans and the inventory of archaeological material. This report is a PDF document that can be freely consulted on the website of Carta Arqueològica de Barcelona, and now of course on this website of the shelters of Barcelona.

- Bibliography

- ACHÓN CASAS, Oriol. 2010. “Mas Guinardó.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2009, p. 78–81.

- ACHÓN CASAS, Oriol. 2011. “Jardins de Mossèn Costa I Llobera.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2010 (2010): p. 43–44.

- ALBERTÍ, Elisenda. 2004. Perill de bombardeig!: Barcelona sota les bombes (1936-1939). Barcelona: Albertí editor,

- AJUNTAMENT DE BARCELONA ; CLAVEGUERAM DE BARCELONA, (eds). 2002. Atles Dels Refugis de La Guerra Civil Espanyola a Barcelona: 2002. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. Manteniment i Serveis ; CLABSA. [Inèdit]

- ARMENGOU, Montse ; BELIS, Ricard. 2008. Ramon Perera: L’home Dels Refugis. Barcelona: Rosa dels Vents : TV3.

- ARNABAT, Ramon. (ed). 2009. Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial : resum de ponències. Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona.

- ARNABAT, Ramon. 2009. “La defensa de Barcelona. Del relat històric als elements patrimonials.” In ARNABAT,R. (ed.). Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial, Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona, p. 27–54.

- ARNABAT, Ramon ; GESALÍ, David ; IÑIGUEZ, David. 2011. “Defensa 1936-39 / BCN : Guia D’història Urbana.” Barcelona: Institut de Cultura, Museu d’Historia de Barcelona

- 2004. Barcelona Sota Les Bombes: La Ciutat Foradada. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. [Enregistrament de vídeo]

- BENGOETXEA i SABATÉ, Albert. 2005. Sota El Pla de Barcelona: Espeleologia Urbana a L’antic Terme Municipal de Sant Andreu Del Palomar. Barcelona: GERS de l’Agrupació Excursionista Muntanya.

- BESOLÍ, A. 2004. “Los Refugios Antiaéreos de Barcelona: Pasado Y Presente de Un Patrimonio Arcano.” Ebre(Núm. 38): p. 181-202.

- BOSCH, Alfred ; MELERO, Josep. 2007. “Barcelonins! perill de bombardeig!: les bombes de Franco (1937-1939)”. A: Ruta de les llibertats passejades per la Barcelona èpica, Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. Institut del Paisatge Urbà i la Qualitat de Vida, p. 199–209.

- CARBONELL BADIA, Carles. 2010. “LAV Mallorca / Torre Del Fang.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2009, p. 70–73.

- CARDONA ESCANERO, Gabriel. 2009. “Els atacs aeris sobre Barcelona en el context de la guerra aèria, 1936-1945.” In ARNABAT,R. (ed.). Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial, Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona, p. 9–16.

- “Catalunya Sota Les Bombes: Els Atacs Franquistes Durant La Guerra Civil: Monogràfic Especial.” 2008. Sàpiens.

- COLÁS BENEDICTO, Carles. 2014. “Refugi Antiaeri Núm. 1513. Carrer de Juan de Sada.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2012, p. 142–143.

- CONTEL, Josep M. ; TALLER D’HISTÒRIA DE GRÀCIA. 2008. Gràcia, Temps de Bombes, Temps de Refugis: El Subsòl Coma Supervivència. Barcelona: Taller d’Història de Gràcia.

- FABRÉ, J. 2002. La contrarevolució de 1939 a Barcelona. Els que es van quedar. Bellaterra: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona [tesi doctoral]

- FABRÉ, J. 2003. Els que es van quedar. 1939. Barcelona ciutat ocupada. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat

- FORCADES VIDAL, Lourdes. 2016. “Refugi Antiaeri Número 173.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2014, p. 185–88.

- GEA BULLICH, Miquel. 2015. “Refugi antiaeri núm. 1513. Carrer de Juan de Sada.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2013, p. 114–115.

- GESALÍ, David ; IÑIGUEZ, David. 2009. “La defensa passiva i activa de Barcelona, 1936-1939.” In ARNABAT,R. (ed.). Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial, Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona, p. 17–26.

- HINOJO GARCÍA, Emiliano. 2011. “Fàbrica Oliva Artés. Refugi Núm. 882.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2010 (2011): p. 41–42.

- MAESE FIDALGO, Xavier ; VIVANCOS SOLIS, Lluís. 2017. “La Unitat Del Subsòl Dels Mossos d’Esquadra I El Servei d\'Arqueologia de Barcelona: Una Col.laboració de Present I de Futur.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2015 , p. 20–27.

- MIRÓ i ALAIX, Carme. 2009. “Emprentes de La Guerra a La Ciutat de Barcelona.” La ciutat i la memòria democràtica: espais en lluita, repressió i resistència a Barcelona, 20 i 21 de novembre de 2008: p. 21–45.

- MIRÓ i ALAIX, Carme ; RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi. 2009. “Cronotipología dels refugis antiaeris de Barcelona.” In ARNABAT,R. (ed.). Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial, Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona, p. 55–66.

- MIRÓ i ALAIX, Carme ; RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi. 2012. “Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona (1936-1973) Una nova visió des de l’arqueologia d’intervenció.” Ex novo: revista d’història i humanitats(7): 55–79.

- MIRÓ i ALAIX, Carme ; RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi. 2016. “Els refugis antiaeris a la Sagrera.” Tota la Sagrera, núm. 165, p. 10.

- MIRÓ i ALAIX, Carme ; RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi. 2017. “Los Refugios Antiáereos de Barcelona Durante La Guerra Civil Española. Nuevas Aportaciones Desde La Arqueología.” In La Granja San Ildefonso, Segovia. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B1hiVpuEkQdsaVlsdjdJamxYY00(October 31, 2017).

- MORET PUJOL, Lourdes. 2017. “Refugi Antiaeri.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2015, p. 167–68.

- PÀMIES GUAL, Dídac. 2011. “Passeig de l’Exposició, 16-20, Carrer de Tapioles, 77-79, Carrer Del Poeta Cabanyes, 88-89.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2008, p. 32–33.

- PÀMIES GUAL, Dídac. 2017. “Refugi Antiaeri Número 722.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2015 (2015): p. 173–74.

- PÀMIES GUAL, Dídac ; MORET PUJOL, Lourdes. 2017. “Refugi Antiaeri Número 441.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2015, p. 169–72.

- PROGRAMA PER AL MEMORIAL DEMOCRÀTIC (Catalunya). 2008. Quan Plovien Bombes: Textos Literaris Catalans Sobre Elsbombardeigs de Barcelona = Quando Piovevano Bombe: Testi Letterari Catalani Sui Bombardamenti Di Barcellona. [Barcelona: Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament d’Interior, Relacions Institucionals i Participació. Memorial Democràtic].

- PUIG i VERDAGUER, Ferran. 2010. “Intervenir als refugis antiaeris de Barcelona.” MUHBA Butlletí, núm.19: p. 3.

- PUIG i VERDAGUER, Ferran. 2009. “L’arqueologia dels refugis antiaeris de Barcelona.” In ARNABAT,R. (ed.). Els refugis antiaeris de Barcelona: criteris d’intervenció patrimonial, Barcelona: Institut de Cultura. Museu d’Història de Barcelona, p. 69–79.

- PUJADÓ PUIGDOMÈNECH, Judit. 2008. El Llegat Subterrani. Badalona: Ara Llibres.

- PUJADÓ PUIGDOMÈNECH, Judit. 2006. Contra l’oblit : els refugis antiaeris poble a poble. Barcelona: Publiacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

- PUJADÓ PUIGDOMÈNECH, Judit. 1998. Oblits de Rereguarda: Els Refugis Antiaeris a Barcelona, 1936-1939. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

- PUJADÓ PUIGDOMÈNECH, Judit. 2008 ; MUSEU D’HISTÒRIA DE LA CIUTAT (Barcelona). 2007. Ciutadans Sota Les Bombes. Barcelona: Museu d’Història de la Ciutat

- RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi. 2014. “Refugi Antiaeri Núm. 547. Carrer de Fernández Duró.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2012, p. 139–41.

- RAMOS RUIZ, Jordi ; RAVOTTO, Alessandro. 2011. “Plaça de Les Navas.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2008, p. 79.

- SERVEI D’ARQUEOLOGIA DE BARCELONA. 2010. “Refugi Núm. 374.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2009, p. 165.

- VICENTE GARCIA, José Manuel ; VIAMONTE SOLÉ, Mònica. 2011. “Carrer de La Riereta, 4, Carrer de Vistalegre, 11.” Anuari d’Arqueologia i Patrimoni 2008, p. 61–65.

- VILLARROYA i FONT, Joan. 1999. Els Bombardeigs de Barcelona durant La Guerra Civil. 2a ed. Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat.

- VILLARROYA i FONT, Joan ; PUJADÓ PUIGDOMÈNECH, Judit ; POWLES, V. 2002. El Refugi 307: La Guerra Civil i El Poble-Sec, 1936-1939. Barcelona: Ajuntament de Barcelona. Consell Municipal del Districte de Sants-Montjuïc.

Credits

Regidoria de Memòria Democràtica

- Original idea and concept: Carme Miró, Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

Marta Fàbregas, Jordi Ramos, Atics s.l. - Project coordination: Carles Vicente. Director de Memòria, Història i Patrimoni

Carme Miró. Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona - Scientific direction: Carme Miró i Jordi Ramos

- Art direction and graphic design: David Solà. Edittio

- Content creation and writing: Silvia Marimón

- API project direction: Sergi Fernandez. Apiumhub

- API implementation: Piotrek Majchrzyk. Apiumhub

- Support in creating and implementing the API: Christian Ciceri. Apiumhub

- Programming WP & frontend: Tomàs Jimenez, Alex Polonsky. oranginalab

- Image research and documentation: Encarna Cobo i Jordi Ramos

- Documentation and database: Marta Fàbregas, Laia Gallego i Jordi Ramos. Atics, s.l. i Xavi Maese, Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

- GIS technician: Alex Moreno, Laia Gallego. Atics s.l.

- 3D Models: Joan Garcia Biosca

- Proofreading and translation: Tau traduccions.

- Map: Plànol de Barcelona, 1935. Ajuntament de Barcelona. Oficina del Pla de la Ciutat.

- Collaborations and references:Josep Pujades

Josefa Huertas

Unitat de Subsòl. Mossos d´Esquadra - Archives consulted:

- Archivo General Militar de Ávila

- Archivo Histórico Nacional

- Biblioteca Nacional de España

- Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica (Salamanca)

- Arxiu de l´Abadia de Montserrat

- Museu d´Història de Catalunya

- Centre d´Informació i Documentació del Memorial Democràtic

- Filmoteca de Catalunya

- Pavelló de la República. Universitat de Barcelona

- Arxiu Nacional de Catalunya

- Centre de Documentació del Servei d’Arqueologia de Barcelona

- Arxiu Municipal de Barcelona

- Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona

- Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

- Arxiu Contemporani Municipal de Barcelona

Memory

Barcelona's air raid shelters were built by citizens or the administration with the aim of protecting against the brutal air bombardment suffered by the city during the Civil War, and are part of our heritage and collective memory, and have become symbols of popular self-organization, resistance and struggle. For these reasons the shelters have also been the subject of neighborhood claim campaigns for their conservation and documentation.

In this interactive website promoted by the Department of Democratic Memory and the Archaeology Service of the Barcelona City Council we make available to the public all the information that we currently have of each of the documented shelters.

You will find research carried out over 20 years by various specialists. However, we do not consider the work to be completed, on the contrary, with this website we concentrate all the information to put it at the service of citizens, as we did years ago with the Carta Arqueològica de Barcelona; and also as with the chart, it is necessary a constant renewal, adding all the new discoveries and searches.

That is why we call on everyone who is interested and has information, and who wants to share it to contact us.

Enter and surf the map. You will surely discover a new way of observing and perceiving our City. You also have information about what to do when documenting a shelter, how archaeologists work in their documentation, and about the historical context in which these confined structures had to be built, creating an underground city to flee the horror of fascist bombing.

Regidor de Memòria Democràtica