CHRISTIANITY | Where does the Christmas spirit blow?

Cause I lost my job

And I talked to Jesus at the sewer

And the Pope said it was none of his God-

damned business

Sixto Rodríguez

Christmas is the season of gifts. Almost overnight, cities across the Western world (and beyond) slip into a kind of trance: bright lights and brash decorations go up, and grown adults don costumes to conjure a magical realm. For a few days, we let ourselves be swept along by a surge of generosity. A torrent of cultural products branded as “Christmassy” –films, songs, stories, ornaments, etc.– flood the streets and shopping centres, schools and government offices, streaming platforms and cinemas. A message of inevitably saccharine goodwill circulates everywhere, with and without a religious tone, until that generosity shifts into something closer to compulsion. Each year the Christmas frenzy exposes its starkest face in consumerism and sales campaigns a little earlier, to the point of almost eclipsing the celebration of the birth of God made flesh.

Even so, Christmas remains a Christian celebration, and whether one likes it or not, in a society that largely sees itself as secular, many Christmas customs cannot be fully understood without considering the Catholic culture embedded in each society, in our case, Catalonia. In what follows, I will approach the spirit of Christmas from multiple angles, taking particular note of the tensions that accompany the season’s often unbridled altruism.

To do this, I will follow an old anthropological fascination: tracing the path of offerings. In which directions do Christmas gifts flow? From a Christian perspective, the heart of Christmas is guided by charity –agápē, or Christian love– one of the three theological virtues, grounded in unconditional giving that goes beyond what is deserved. In that sense, it differs from solidarity. Christian love is not bound by moral rules; it is not practised out of obligation or in the name of justice, but as an expression of communion, particularly with the marginalised and the outcast, for whom the Jesus of the Gospels showed special preference. Yet, of the three theological virtues (the others being faith and hope), charity is the one most easily entangled with earthly inequalities. Its most tangible expression is the gift. For that reason, I propose examining a series of examples in which gifts reveal how charity takes on different social forms depending on the context. Who is in a position to give or receive gifts? And what meaning is attached to them?

Gifts are primarily intended for children, the true stars of the celebration. I would like to start by recalling an old 19th-century Christmas tale collected by the Brothers Grimm, The Star Money (Die Sterntaler), in which the “natural” order of giving is turned on its head: it is a little girl who gives (though she also ends up receiving). The tale tells of an orphan girl with no home, who owns only a piece of bread and the clothes on her back. As she walks through the fields, she encounters other children even worse off than herself. First, she gives her bread to one who is hungry, and then she offers her clothing to those shivering in the cold. Suddenly, alone and naked in the middle of the forest, the stars from the sky fall upon her, transformed into silver coins. Following this miracle, she will be rich for the rest of her life[1].

To put the story in context: the Brothers Grimm came from a bourgeois Lutheran family and were raised in the Hesse-Kassel region, in what is now central Germany. Contrary to popular belief, the Brothers Grimm did not collect their tales by travelling from village to village. Most of the stories they recorded were told to them by women in their social circle, during literary gatherings held at their home. Two of their most notable informants were Marie Hassenpflug and Dorothea Viehmann, both from families of Huguenot emigrants, French Calvinists exiled after Henry IV issued the Edict of Nantes in 1598.

The miracle in The Star Money, where the protagonist’s charitable acts are rewarded with wealth, brings to mind Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Weber’s argument, summarised roughly, suggests that capitalist accumulation and the emergence of a bourgeois class require a prior ascetic, vocational discipline, which leads producers to reinvest their earnings in work rather than enjoy them. In this sense, prosperity becomes a mark of faith, much like it does for the pious orphan in the story. Weber saw this type of asceticism as typical of Reformed churches, citing the Huguenots as a prime example. Later, I will revisit the difference between Protestant and Catholic approaches to Christmas charity.

Let’s look at other examples closer to home, involving children, the main recipients of gifts. As in any celebration, social hierarchies are blurred at Christmas, and this also affects the distinction between adults and minors. Children, in their role as dependents, assert a temporary subversion of the established order. Student and youth festivities, beginning on St. Nicholas of Bari’s day (6 December), the patron of children, anticipate the Christmas season and reflect this playful, transgressive spirit. Also on St. Nicholas’s Day, at Montserrat Abbey, a “bisbetó” or “bisbe caganiu” (boy bishop) was traditionally appointed, where for one day a choirboy would dress and act as an ecclesiastical authority. These celebrations, now largely forgotten, once took place throughout Christendom between St. Nicholas’s Day and the Feast of the Holy Innocents. In Spain, it was called the Fiesta del Obispillo, and in France, Abbas Stultorum. Symbolically, they are linked to the irreverent Feast of Fools; although one should be careful about equating such distinct customs, they evoke the Saturnalia, the pagan orgiastic celebrations of Ancient Rome held around the winter solstice, before the Christian calendar was established.

Although it would be misguided to link Christmas with a pagan, carnival-like festival. Christmas is a season in which roles are reaffirmed rather than overturned. And, as I intend to show, this is even more evident in the Catholic world, where gifts are invariably bestowed by figures of authority. Perhaps the Feast of the Holy Innocents is the only date on which a mild, and almost expected, disruption of order persists. Let’s remember that the Feast of the Holy Innocents commemorates the infanticide carried out by Herod in Bethlehem, an episode that hardly seems suitable for jest. So why is it precisely on this day that we celebrate by playing pranks on one another? It is hardly surprising that this custom is not widespread among all Christians (indeed, it cannot really be linked to either Catholics or Protestants[2]); it appears only in Spanish-speaking countries. Despite this oddity, if we follow the thread of children’s revolt through to the inversion of the gift found in the tale of The Star Money, we might imagine it as a symbolic act of vengeance for the tragedy recounted in the Gospel.

Connected to this spirit of defiance, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss published Father Christmas Executed in 1952. In it, he reproduces a press report describing how, in Dijon cathedral, and before 250 children from a poorhouse (many of them probably orphans of the Second World War), a figure of Father Christmas was first hanged and then burned. This symbolic execution was intended as a protest against the growing paganisation of Christmas, at a moment when France was becoming increasingly Americanised under the influence of the Marshall Plan. The episode, striking enough on its own, allowed Lévi-Strauss to draw parallels between Christmas and the rites of passage found in Amerindian tribal societies.

Lévi-Strauss’s argument centres on the idea of secrecy[3]: the transition from childhood to adulthood, as in Amerindian rites of passage, takes place when knowledge reserved for part of the community is disclosed, in this case, the Christmas myth carefully constructed by parents. The Belgian anthropologist pushes the comparison even further (for my taste, perhaps a little too far), suggesting that children, in their socially ambiguous state, humans who are not quite fully human, occupy the role that ancestors once held in Amerindian cultures, ancestors to whom gifts had to be offered in order to fend off death. Seen through this lens of ancestor-veneration, the gifts are given less to delight the children than to enable adults to confront an age-old, deep-seated fear..

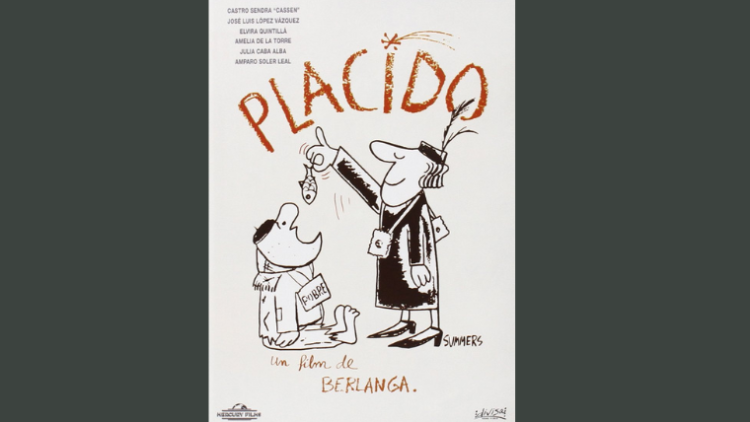

Still, if we pay attention to the pattern of gift-giving in a Catholic Christmas, we often see that it underscores hierarchies that run vertically, from those above to those below. Children, within the Christmas imagination, receive gifts because they are counted among the vulnerable, those who need assistance and whose presence lends the season a sense of moral renewal. Christmas hampers, the Christmas bonus… The flow of Christmas gifts mirrors social imbalances, simply inverted. This dynamic is wonderfully depicted in Plácido (Luis García Berlanga, 1961). The film is a grotesque satire built around a Christmas campaign in a provincial town, launched under the slogan “seat a poor person at your table”. Beneath the colourful cast of characters, we glimpse a distinctly Francoist strain of ill humour, where blatant hypocrisy is breezily accepted in the name of Catholic charity.

If we compare it with another classic film, It’s a Wonderful Life (Frank Capra, 1946), we find a very different message. James Stewart plays an honest businessman who, on Christmas Eve, considers jumping off a bridge because of a tax debt. Through the intervention of an angel, he comes to realise that life is worth living because he is loved. When his wife discovers his predicament, she asks for help, and the entire town rallies to her home, freely offering what they can and relieving James Stewart of his financial burden. A distinctly American message: if you are good, the angel of capitalism will save you. God is strict, but he will not crush you. Or perhaps a Protestant message, as in the tale by the Brothers Grimm about the orphaned girl, where the miracle at the end is money. Yet here, the real miracle does not descend from heaven, it springs from the generosity, affection, and sense of community of neighbours.

This is why, in much of the Protestant world, the unexpected persistence of spirits of nature is striking (with Father Christmas as a prominent figure): they act as mediators of Christmas gifts, which seems at odds with Weber’s notion of the triumph of the world’s disenchantment. Yet their relative indifference to the social order could be seen as consistent with the democratic impulse associated, at various points, with the Reformation. Indeed, these spirits eventually became established while being domesticated alongside the commercial reconstruction that took place in the United States, arguably the first foundational modern democracy to flourish and a key centre for the renewal of the capitalist ethos. The figure of Santa Claus would later be projected globally, even appearing as Père Noël in secular France, still marked by its residual Catholic heritage, in the youth of Lévi-Strauss.

In the film Miracle in 34 Street (George Seaton, 1947), released in Spain as De ilusión también se vive, this transformation is perfectly illustrated. In a fantastical legal case reminiscent of a citizen’s perspective on the Inquisitor in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the court is asked to determine the authenticity of a character whom the audience believes to be the real Father Christmas. Unlike the Inquisitor, during the trial, the State of New York ultimately rules that, for social, economic, and moral reasons, Santa Claus does indeed exist! Beyond the court’s decision, the film’s verdict on Santa Claus’s continued relevance in the twentieth century is delivered by a child: Natalie Wood, playing the role of the devil’s advocate. In a new inversion of the gift-giving order, the girl helps her mother organise the Christmas parade and distribute presents, all the while remaining firmly sceptical of Christmas magic. Only the granting of her wildest wish (a new house) turns her into a believer, simultaneously rewarding her moral consistency and giving a fresh twist to the tale by the Brothers Grimm.

Finally, it is tempting to interpret the “tió” from this perspective. The surprising survival of Christmas mediating spirits in a Catholic society might be more than just another expression of a supposed eschatological –and perhaps, in a psychoanalytical sense, childlike– tendency in Catalan collective psychology. The Christmas log could be seen as a gift that is not bestowed directly by authority, but emerges from the earth itself, and only when prompted by the youngest children. The blows struck by the children suggest a playful irreverence; asking for miracles with the swing of a stick hardly fits with the usual harmony of Christmas. Perhaps the ritual creativity expressed through the children’s actions challenges authoritarian generosity, pedagogically hinting that the most meaningful rewards are earned through effort.

[1] Notice that this story is a devout (and Calvinist) variation of a myth found in both Eastern and Western philosophy. Such tales typically depict a sage pursuing peace through humility. In ancient Greece, for example, there were stories about the Athenian cynic Diogenes. A Buddhist tale tells of a sage who owned nothing but a single bowl and meets a wanderer who needed only a banana peel to eat. Realising this, the sage smashes his bowl against a stone. Calderón de la Barca popularised a poem that reads: “Of a sage, who roamed dejected / Poor, and wretched, it is said, / That one day, his wants being fed / By the herbs which he collected. / Is there one (he thus reflected) / Poorer than I am today? / Turning round him to survey / He his answer got, detecting / A still poorer sage collecting / Even the leaves he threw away”.

[2] In this article I place greater emphasis on the distinctions between Catholic and Protestant Christmas traditions than on the differences between individual national celebrations. For instance, consider the importance of Epiphany here compared with Portugal, our neighbouring country, where the day is barely celebrated at all. Examining all of this in detail would go beyond the scope of this text. I will add only one suggestive example in this regard: the various names used across Catholic countries in Europe to refer to the cult of Mary: Mare de Déu (Catalonia), la Virgen (Spain), a Nossa Senhora (Portugal), Madonna (Italy), Notre-Dame (France).

[3] The interplay of secrecy and Christmas has inspired some fascinating anthropological studies; For instance, see Manuel Delgado’s preface to the Catalan edition of the Lévi-Strauss text mentioned earlier. This is hardly surprising: the revelation of Christmas secrets is often remembered as symbolically unsettling. In an instant, an entire mythical universe shared by children comes crashing down. When the Three Kings are unmasked, they take with them a whole divine constellation: from the Tooth Fairy to gnomes, fairies or any other magical beings that exist only in the imagination of children.