#NITRELIGIONS | Four religious communities knock on the MUEC's door to engage in dialogue about its pieces

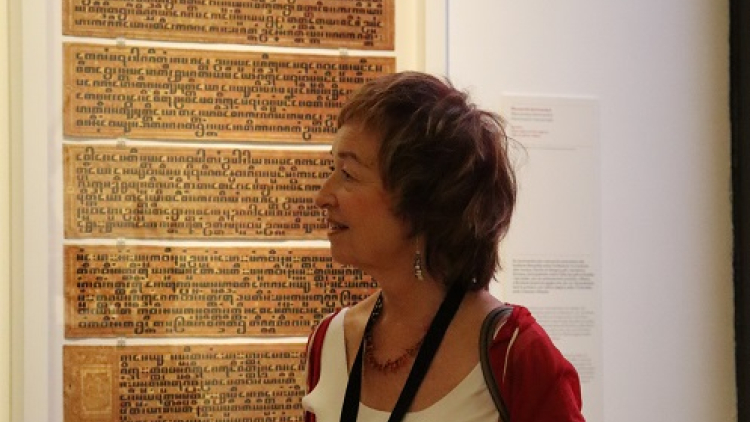

On Saturday 14 September, the Montcada branch of the Ethnological Museum and Museum of World Cultures (MUEC) hosted the activity ‘Heritage and living religions: Barcelona's communities at the Museum of Ethnology and World Cultures’, co-organised by the Office for Religious Affairs (OAR) and the MUEC as part of the Night of Religions. It consisted of tours of the collections on Hinduism, Buddhism, Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and the Yoruba tradition guided by people belonging to these communities.

Museums are places of encounter between culture and citizens, making them the ideal place for engaging in a dialogue between the reality of society and its past. This dialogue becomes even deeper when it includes religions and reveals the connections over time both within the same community and among different human groups. The activity ‘Heritage and living religions: Barcelona’s communities at the Museum of Ethnology and World Cultures’, co-organised by the Office for Religious Affairs (OAR) and the Museum of Ethnology and World Cultures (MUEC), precisely aims to underscore these connections between the city’s religious plurality and the roots of the communities that comprise it.

It consisted of two visits: one to the Asia collection and the other to the Africa collection, where people representing Buddhism, Hinduism, Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity and the Yoruba cult in Brazil commented on different objects and religious figures from their respective beliefs. However, the activity began with a docent’s brief contextualisation about the museum, which was founded in 2017 from the merger of the Barcelona Ethnology Museum, the Ethnography and Colonial Museum and the Museum of World Cultures. It is divided into two branches, one on Montjuïc and one on Montcada. The latter houses collections from Africa, Asia, Oceania and the Americas which stem from the collaboration between the businessman and collector Albert Folch and the sculptor and Ethnology Museum collaborator, Eudald Serra. Starting in the 1940s, Folch and Serra took a series of journeys ‘with an eye on an exoticism clearly based on racism. They visited places like Equatorial Guinea, Tibet and Cambodia to purchase pieces,’ which gave rise to the collections housed today in the Montcada branch of the MUEC, where the activity was held.

‘Today’, the docent continued, ‘the Museum’s goal is to be aware of this past, so we always trace the origins of the pieces.’ This contextualisation also comes from activities like the one held on 14 September, which continued with the presentation of some of the pieces from Hinduism by Nayan Das, of the Hindu Cultural Association of Barcelona. Krishna was the introductory figure, ‘the head of creation, the one who observes and expands his energies in the guise of avatars who do his bidding’. The next step was the stele of Vishnu and Lakshmi atop Garuda (Rajasthan, India, fourteenth to sixteenth centuries), in which Vishnu, the avatar in charge of creation, appears with Lakshmi, his wife and female energy, the goddess of maintenance. Nayan Das also presented the sculpture of Shiva and Parvati and talked about Shiva, ‘the destroyer, the Mahadeva or great god’, who is next to the sculpture group of Durga slaying the buffalo demon (Himachal Pradesh, India, fourteenth to fifteenth centuries), who is depicted here with four arms, even though she has ten, each with a weapon.

The visit to the collection on Buddhism was led by Glòria Puig, president of the Catalan Coordinator of Buddhist Entities, who explained the figure of Buddha via different pieces. Born Siddhartha Gautama, he was the prince of what is today a region of Nepal who lived in complete ease until he saw disease, death and poverty for the first time on a visit to the city and decided to devote his life to finding the way to overcome suffering. After studying with different masters, he retreated to the mountain to meditate in a state of total asceticism. ‘He did not eat or drink, he slept on a bed of thorns… He was emaciated, he looked like a skeleton’, said Puig in front of the piece called Historic Shakyamuni Buddha Fasting (Afghanistan, second to third centuries), which represented this precise state of Buddha. But he did not find enlightenment until he went back to a less radical form of asceticism. There are many sculptures in the collection that depict that moment, when Buddha has one hand on his lap and the other touching the ground, ‘the mudra (position) of enlightenment (like the Bhaisajyaguru Medicine-Buddha, Tibet, eighteenth to nineteenth century), a gesture that shows that he is posing on the ground as a testimony of his effort’. Puig also presented figures that show other keys to Buddhism, like androgynous figures that indicate overcoming the man-woman dualism (like the Cakrasamvara Joined to his Consort, Dakini Vajravārāhī, Nepal, sixteenth century) and the Buddhas of compassion, which have more than two arms.

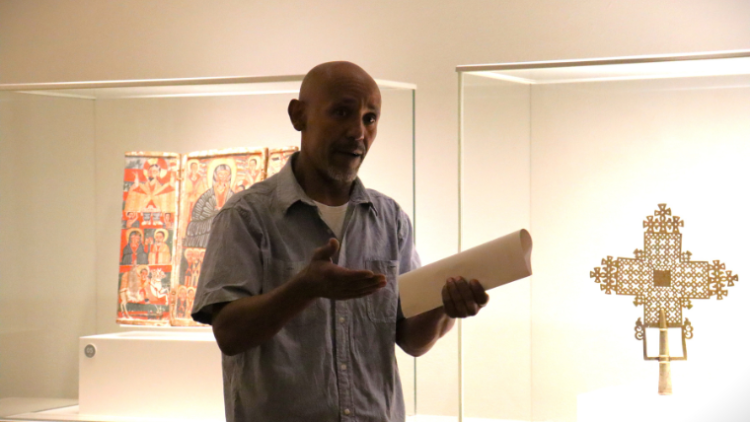

The tour of the collection on Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity was led by Ayalkibet Hundesa, who is not a practitioner but comes from a milieu that is profoundly involved in this belief. The visit was primarily focused on presenting three crosses. Two of them are processional crosses (eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), artefacts that are used in different celebrations which are different for each church, given that they ‘bear symbols that identify the church to which they belong’. The third cross, a wooden ‘hand cross’ (Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) is an example of a type of painted wooden cross that Ethiopian Orthodox priests always carry with them, which ‘believers greet and thank whenever they cross pats with a priest on the street’. To conclude, Hundesa explained that the Ethiopian Orthodox church has its own language, called Ge’ez: ‘If you’re not practising and one day you decide to go to church, you won’t understand anything’.

The activity’s last visit was to the collection on the Yoruba Condomblé tradition in Brazil, presented by Luis Fernando Brito Fernández, a Babalorixá (priest) in this cult. The Condomblé tradition was created in Brazil due to the African diaspora prompted by the slave trade, which imported the beliefs of the Yoruba people, a large ethnolinguistic group from West Africa, to the Americas, where it took root via orality, given that ‘the slaves didn’t know how to write’. Condomblé, specifically, is based on the soul and the power of nature. Brito Fernández exemplified this by presenting the figure of Oshun, the goddess of fresh water and rivers (Nigeria, 1920), of whom he was initiated as a Babalorixá: ‘I did not choose Oshun; Oshun chose me when I was in my mother’s belly’. She is the goddess of rivers and fresh water, but also of love, beauty, life and the female force. All of this is depicted in the wooden sculptural group in which the goddess, a black woman with a feather on her head indicating that she is menstruating, is feeding several children in a river, with fish on her lap and surrounded by animals.

The Babalorixá also mentioned the historical context of the birth of Condomblé: ‘For a long time, believers had to pray to their gods while hiding beneath Christian saints’. But the Yoruba tradition is still misinterpreted even today: ‘We are labelled orcerers and people say that we do fortune telling. But actually, what we Babalorixá do is guide people, usually with artefacts like this one’, he said, pointing to a wooden Ifá divination tray (Benin, nineteenth to twentieth centuries). The conclusion of the day was that this is why activities like this one make sense now, because they make room for religious communities to engage in dialogue with citizens and even influence the way their customs and practices are disseminated, which are their heritage both inside and outside the museum.