As a defensive structure, the sea-facing wall protected the coastal flank against possible attack from the sea. This was the case when the forces of Philip V, in an attempt to retake Barcelona from the archduke Charles of Austria in 1706, bombarded the castle from the sea while also attacking it by land. With the arrival of the allied navy of Charles III, Philip V was forced to retreat in 1708. The archduke decided to strengthen the maritime flank, as proved by the words of the military engineer and architect of the subsequent siege of Barcelona in 1714, Prosper de Verboom: “[the Barcelonans] do not cease in their efforts to obtain a better defensive position [...], they have prepared all the heights of Montjuïc, where they work with great determination on the construction of new fortifications, particularly on the highest point, which corresponds to the western bastion overlooking the sea and the beach below the Llobregat tower, and the eastern bastion overlooking the sea and the city.”

Nowadays, the covered way along the sea-facing wall offers magnificent views of El Morrot, the area occupied by Barcelona’s cargo port, as far as the River Llobregat.

The artillery batteries

On the platforms around the entrance to the castle and the Sant Carles Bastion, a set of artillery pieces remain as a reminder of the period when the castle was used to attac the city and its inhabitants. They were mounted there in 1937 and 1938, originally as antiaircraft batteries to combat the bombing raids of the fascist Italian air force, but were subsequently used for salutes of honour. In 1938 four Vickers guns (model 1923, 152.4/50 mm) were installed, still in place today, although obviously they are no longer operational.

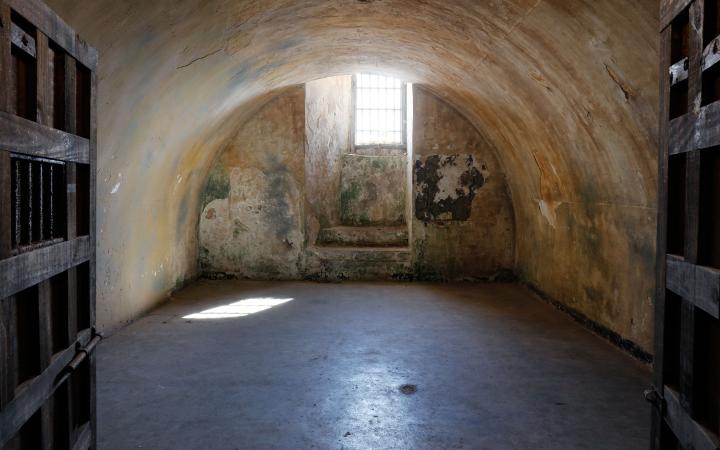

The dungeons

The old castle dungeons are five rectangular cells situated below the rooms on the seaward side of the parade ground. The entrance is now on the outside through the window of one of these rooms, behind which a staircase was built. Originally, however, they were reached by the staircase leading to the chambers in the sea-facing wall and the Sant Carles Bastion. On an intermediate landing, there was a door that opened on to a corridor containing the five rooms.

It seems clear, in view of their location on the seaward side and their structural coincidences with other surrounding buildings, that these spaces now referred to as the dungeons already existed in the early fort and, therefore, were built before Cermeño’s time, although probably for another purpose.

The first inmates were French soldiers taken prisoner during the War of the Pyrenees (1793-1795). Later, during the Peninsular War (1808-1814), those who refused to swear allegiance to José Bonaparte were imprisoned there. It was not, however, until the demolition of the fortress in the Parc de la Ciutadella, the other military prison in the city, in 1868, that the castle took on the role of the main military prison in Barcelona.

Those imprisoned there included federal republicans, the hero of Philippine independence Jose Rizal (1869), anarchist workers held there in 1897 during the trial known as the Procés de Montjuïc, the educator Ferrer i Guàrdia, accused together with four other suspects of instigating the Setmana Tràgica, the so-called tragic week of 1909, and workers arrested during the strike that started at La Canadenca in 1919.