News

Albéniz, don't get involved in politics!

On January 5, 1895, Captain Alfred Dreyfus was officially expelled from the French army in a public ceremony of degradation at the Military School in Paris, in front of the troops and with an angry crowd shouting "traître" and "mort aux Juifs". Dreyfus, an Alsatian officer of Jewish origin, had been accused of being a spy in the service of Germany, the great enemy. He had been court-martialed, found guilty of high treason and would pay for his crime serving life imprisonment in Île du Diable, in the French Guiana, with an exemplary punishment.

But there was one small detail that no one had cared much about during the judicial process: Dreyfus was innocent. His family, with the collaboration of French journalists, politicians and intellectuals, fought against all odds to prove it. The divisions and social tensions of turn-of-the-century France were unleashed around this case: the Affaire Dreyfus transcended the military sphere to become a political and social issue that deeply shook the country.

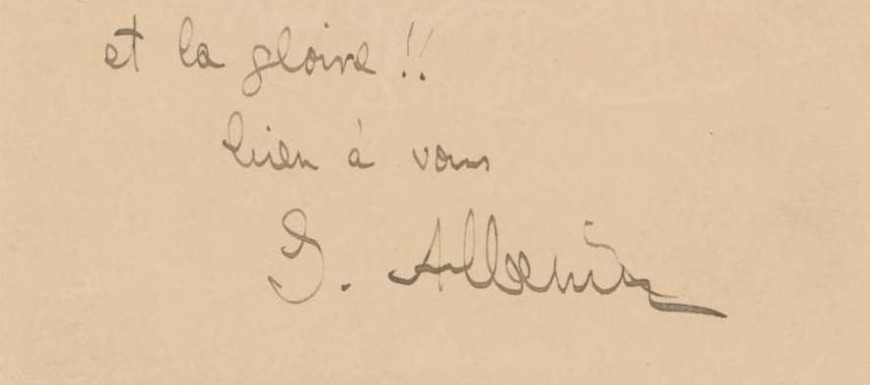

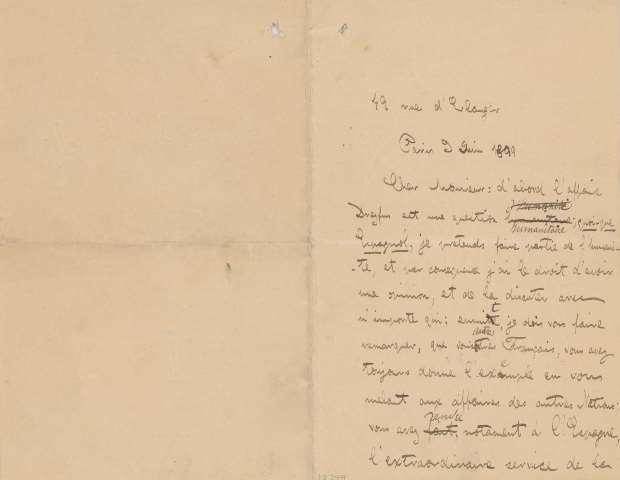

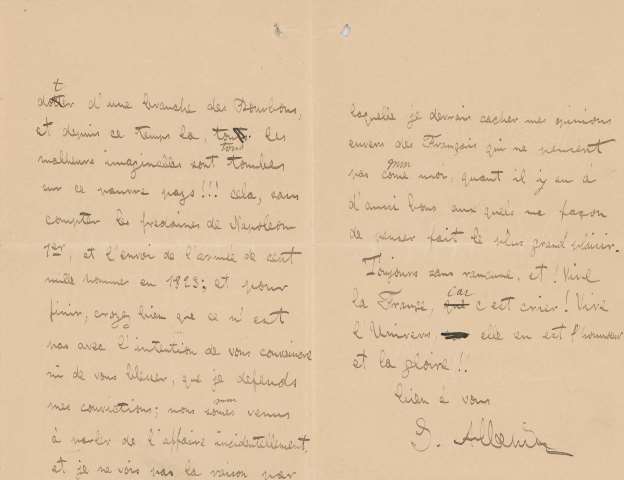

Anti-Semitism and the cultural battles between traditionalism and modernity converged in a perfect storm with effects in all areas. Artists and intellectuals became involved, positioning themselves both for and against the captain's innocence. Isaac Albéniz speaks openly about the affair in a letter to an unidentified correspondent -he was not a close person, since he addressed him as "Cher Monsieur"-, written in Paris on June 9, 1899 and preserved in the Historical Archive of the Museu de la Música (document 10.299 in Isaac Albéniz Fonds).

Albéniz expresses himself bluntly: "[...] the Dreyfus case is a humanitarian issue; although Spanish, I claim to be part of humanity, and consequently I have the right to have an opinion, and to discuss it with any other [...]. The addressee of the letter must probably have reproached him for making public statements about French politics as a foreigner, a common criticism of public figures who are involved in controversial causes or issues unrelated to their profession. Nor does the Camprodon composer fall short in expressing his republican ideas: "[the French] have rendered, especially to Spain, the great service of providing it with a Bourbon branch, and from that moment on, all imaginable misfortunes have fallen upon this poor country! ". However, the letter ends sportily, "without rancour" and with a "Vive la France", a France that for many -like Albéniz- was still the emblem of progress and reason, something that the Dreyfus case had seriously questioned.

The letter is dated June 9, 1899, six days after Alfred Dreyfus left Île-du-Diable for Rennes (Bretagne) where a second court-martial was to review his case in the light of new evidence, the discovery of another officer suspected of being guilty, and the increasingly evident errors, inconsistencies and anti-Semitic biases in the judicial process. Thus, it was a boiling point in the case, which was sure to come up in any conversation or Parisian gathering that Albéniz might frequent.

Albéniz moved in a professional and artistic environment where there were both supporters and detractors of Dreyfus. It is noteworthy that the Schola Cantorum, the musical institution where Albéniz was a professor and which was run by his friend and collaborator Vincent D'Indy, had a clear anti-Semitic tendency. D’Indy even spoke of a "musical dreyfusism", a "Jewish melodic style" or "Jewish school" that composers should avoid (Llano, p. 27-29). Musical aesthetics, then, was also permeable to the political evolution of the affair.

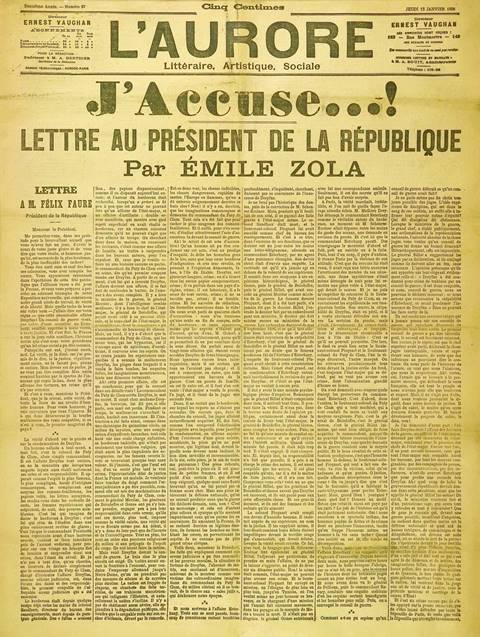

Albéniz's Dreyfusism is also commented on by Henri Collet, a French composer and musicographer, in his biographical book Albéniz et Granados: "We talked a lot about the Dreyfus case. Albéniz, naturally "dreyfusard", regretted the fate of the innocent Israelite ... and this always ended with a bottle of champagne ... "(p. 60). The adverb "naturally" is revealing of how support for Dreyfus was closely related to liberal political tendencies. The anecdote takes place, according to Collet, in 1898, the year that everything changed definitely in the affair. On 13 January 1898 the writer Émile Zola published on the front page of the Republican and Socialist newspaper L'Aurore the famous open letter to the President of the Republic, Félix Faure, with the combative headline J'accuse!. The impact of this front page was crucial to the subsequent development of the case. In September 1899 Dreyfus was pardoned and finally in 1906 he was acquitted and officially rehabilitated.

In short, the Dreyfus affair had an enormous impact on the social and cultural life of France. Albéniz was a direct witness to this and did not hesitate to publicly express his opinions, despite the criticism. For him it was not about politics or aesthetics, but about humanity.

REFERENCES

Collet, Henri. Albéniz et Granados. Collection Les maîtres de la musique. París: Librairie Félix Alcan, 1929.

Llano, Samuel. Whose Spain? Negotiating Spanish Music in Paris, 1908-1929. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Zola, Émile. J’accuse ! et autres textes sur l’affaire Dreyfus, présentés par Philippe Oriol. París: EJL, 1998.