News

Restoration of the Guillamí Cello MDMB C 10488 by the Luthiers of Casa Parramon

We are pleased to announce that the restoration project of Joan Guillamí's cello, built in Barcelona in 1756, owned by the Orfeó Català and loaned to the Museu, has been successfully completed. The collaboration between both entities, Orfeó and Museu, has made it possible for a heritage instrument —which you have all seen welcoming visitors to the permanent exhibition— to regain its musical use thanks to a restoration process that has been ongoing between 2023 (project) and 2024 (restoration), carried out by the luthiers of Casa Parramon.

The instrument is a cello by Joan Guillamí (1702-1769), one of the most prestigious instrument makers in 18th century Barcelona. His instruments are inspired by the models of the famous Italian maker Amati. Born in Barcelona, he established his workshop on Escudellers Street, where he built a number of string instruments made with high-quality woods and varnishes and with great perfection in the finishes. His son, also named Joan Guillamí, continued the trade. He is now considered the most important Catalan luthier, and his works are highly valued. The soundboard, arched and figure-eight shaped, is made of spruce and decorated with purfling. It has two f-shaped sound holes, and the fingerboard and tailpiece are made of ebony. The back, arched, the ribs, and the neck, finished with a scroll, are made of maple. The pegbox is curved.

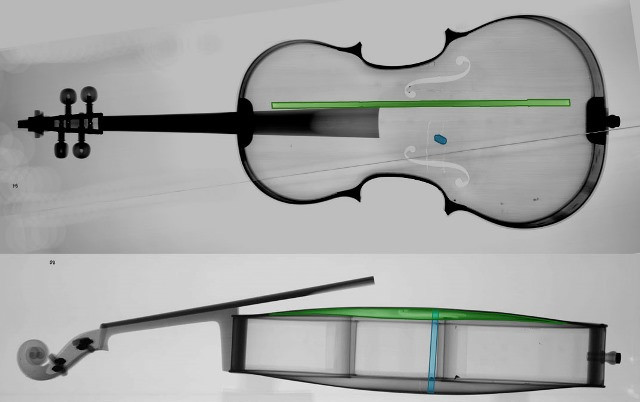

After an analysis by Museum staff, musicians, and luthiers of the instrument's condition and its potential to regain musical use, the first important action was taken: repairing a crack in the back. This was cleaned and reinforced, which took much more work than anticipated because it had been open, separated, and deformed for too many years, forming a V-shape inward. Restoring it to its original shape was longer and more laborious than expected, but we succeeded in consolidating it, creating a custom-made mold to do so.

This cello has a very dense back wood, and probably for this reason, Guillamí made it thinner than usual. Consequently, to reinforce the area of the large crack, we made a long, narrow reinforcement, like a sound post patch, giving it a few tenths more thickness than the original back thickness to prevent future movements and deformations, as it is abnormally thin.

On the other hand, these hidden pathologies, which we did not detect until we opened the back (very worm-eaten area in the upper part at the height of the upper block), have also been repaired, cleaned, and consolidated.

From the outside, before opening, only a single hole was visible, but once opened and from the inside, it was truly alarming. Now, the final step will be to match the color of the new wood on the outside with the original varnish shade of Guillamí.

It is very likely that the cause of the mentioned crack is precisely that in a previous restoration it was closed forcibly with added tensions, as we have detected (and repaired) the beginning of a micro crack on the other half of the back, symmetrically opposed, both coinciding with the end of the lower block, following the grain of the wood.

This is the second and smaller crack in the back, which without being reinforced would have eventually caused problems like the other.

Many instruments, whether violins, violas, or cellos, end up with similar cracks due to an opening of the top or back and subsequent (poor) closure without considering leveling and tensions —unfortunately quite common— so additionally we leveled the upper and lower ends of the back at the blocks' height so that when closing the back finally, it was without added tensions.

We also reinforced internally the worm-eaten areas of the central ribs with light spruce pieces, similar to previous ones that were already there, to give more consistency to the affected area. The upper right rib is very aesthetically deteriorated due to the lack of maintenance over a long period.

It tends to be an area where musicians' sweat, due to constant contact and rubbing of the left hand, penetrates, as it wears down the varnish and ends up darkening and staining the wood, resulting in this gray-greenish discoloration. The vanished varnish ceases to protect the wood. This is not related to the passage of time or aging, but to a lack of maintenance. It is normal to see high-end instruments with worn varnish, but you should never see them with stained and discolored wood.

When musicians wear down the varnish, the wood becomes unprotected, and before reaching these extremes, maintenance of the varnish should be done as often as necessary. This way, the wood would not discolor, nor would deep cleaning and maintenance be needed.

Regarding the setup, we had some doubts in the workshop about the finish. As it came to us and as it was set up, it has a totally eclectic setup, which we assume is the result of many diverse needs over the years.

Right now, as it is, it has the following features:

- Mechanical pegs (practical but heavy), probably from the mid-20th century.

- Modernized neck joint.

- Long modern fingerboard.

- Modern French-style bridge.

- Wooden tailpiece without fine tuners, to accommodate gut strings.

- Gut strings for Baroque playing.

- External spike from the 19th or early 20th century (if it were from the 18th century, there would only be a button).

We see three possibilities:

- Leave it as it is.

- Enhance the Baroque setup.

- Enhance the modern setup.

Based on these doubts and questions, it is Jordi Alomar, director of the Museu de la Música de Barcelona, who indicates, regarding the instrument, historical setup recommendations (for repertoires from the 17th to early 19th centuries) for the following reasons:

- The string tension and materials on the instrument are lower, as well as the pressure from pegs and the sound post, which ultimately can impact the existing fractures (which, although repaired, are always a risk factor in an instrument of this age).

- The potential use for the instrument, if set up for Baroque, will be less aggressive than if used for modern repertoires.

- There are few (or almost no, as I have no other case records) instruments of these characteristics available for institutional use —that is, not owned by musicians for personal use— with a setup prepared for historically informed performance. This is a comparative disadvantage for the many highly skilled performers specializing in this approach and for the original repertoires from the period when the instrument was conceived and built, thus providing opportunities to approach it with maximum care. As a future project, having such an instrument is a qualitative distinction compared to other entities with similar quality instruments. I think of performers like the winners of the Leipzig Bach Competition, among others.

- One last reason is that this setup most closely resembles the original constitution of the instrument.

With the restoration completed despite some unexpected complications but with an optimal result, all that remains is to hear this cello in concert again.