Research projects

The player piano and the four object women

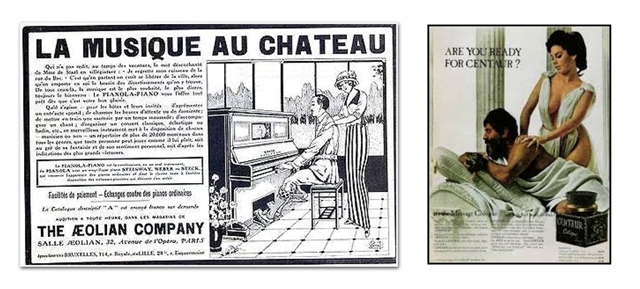

As a phenomenon of great social importance, the player piano had a large-scale media apparatus that, between 1900 and 1930, led to it being featured in the first big international advertising campaigns for a musical instrument. This is of particular significance, since the player piano media phenomenon encompassed several factors that are particularly important for understanding certain marketing strategies that still hold true today. Many of the player piano posters are inspired by Art Nouveau aesthetics where, in the hands of artists such as Jules Chéret and Alfons Mucha, the female figure takes on an undeniably erotic charge and the pretty, stylised image is shamelessly used as an advertising lure, which is why it has often been considered a clear predecessor of the modern poster. When we look at these posters and study the presence of the female figure, we can see four clearly represented thought patterns, all reflecting an openly sexist society whose legacy is still present today.

The first of these thought patterns is the principle of submission to male authority, a submission that is economic, social, moral and bodily. In these posters, the woman is often depicted begging her husband to buy her this new technological wonder called the player piano. As a luxury object in an upper-class home, the player piano would allow this model wife to be part of the typical late Romantic image, where the amateur pianist plays the piano at home, privately or for the enjoyment of family and guests. This is, in fact, one of the most common scenes on player piano posters: the image of a high-society party where the music comes from the player piano, which is always played by a woman. Thus, this submission also became social: from a Chopin prelude to the more modern ragtime, the vast player piano repertoire represents a menu where—if I may make a culinary analogy—the woman is the cook who serves up the musical entertainment for the affluent family. In this way, the object—or rather, the advertising for it—targets the subconscious with a whole model of social conceptualisation and does so by killing two birds with one stone: first of all, by placing the woman in a controlled exhibition space, always at the service of the man, reinforcing a clear model of androcentric superiority. Secondly, this idea is reinforced by insinuating that the man is doing something more than buying an object for upper-class entertainment, as the player piano also arouses men’s socially desirable interest in mechanics and technology. The possession of the machine as a symbol of authority; the possession of the machine and the woman… just look at the later advertising models in the automotive industry. This is, therefore, a design where the market values are carefully studied and the female image is used to develop a web of meanings that are subtle, and at the same time have great subliminal power. This strategy was highly lucrative and became deeply rooted in modern advertising.

The second model represented is much less subtle, however: that of intellectual denigration, conveying the message that ‘anyone can do it’ (even a woman!). As we can confirm, in the decades following the age of the player piano, this model reached extremes that would be inconceivable today.

This intellectual denigration leads us to a third intention or strategy, which is false empowerment: the woman in the player piano posters is encouraged to play an instrument that, unlike a conventional piano, does not require great instrumental technique, making it possible to play music on it quite easily, in the same way a professional would (a man, it is understood). Thus, the slogan ‘anyone can do it’ becomes ‘you can do it!’ (note the entirely intentional italics on the poster) which, within a few years, we would see as the iconic ‘we can do it’, the symbol of a woman who works, but who is still subordinate to male power and authority. Once again, the shameful subsequent use of the icon of working women in the field of advertising reminds us of the dominant social interpretation of this supposed female empowerment.

Finally, we have the last model, a fourth strategy that points directly to the objectification of the female image; a female image that becomes an object of desire, of insinuation and potentiality in the dance and party scenes we mentioned at the beginning. In these posters, the woman plays the piano surrounded by people in a festive spirit and, often, she is the focus of scenes where, despite the clearly festive context, there is an aspect of potentiality, since the people shown in the poster remain motionless, as though listening to a concert. In some of these cases, this potentiality may represent another interesting advertising strategy, one that insinuates that the real party will come afterwards. The context of the neat, tidy upper-class home has the potential to later develop into a party, where everything not shown in the poster is more than clear in the mind of the potential buyer. In this association of ideas that form part of the marketing strategy, the graphic advertising of the player piano uses the female image as an essential vehicle to suggest, to connote everything that could happen beyond the socially established limits.

The player piano advertising posters thus offer a very interesting perspective for analysing the first discourses that objectified the female image, imbuing it with an openly sexist symbolic charge, the reflection of a society in which this positioning would enjoy total immunity up to the present day.