Research projects

Vinyl postcards

You grab your smartphone, open the messaging application, press the microphone icon, record a voice message and send it. Technology at the service of needs, or fashions, has made it easy for you to record your own voice. Perhaps we don’t understand how it works, but we know it's simple. Emailing the link of a song we find on Spotify or any other platform or sending a voice message to mobile messaging is a totally modern action… or not.

These days, messaging services include the functionality of creating short voice messages that are sent to a recipient, but rather than an attempt to create a personal presence, it’s more like just being too lazy to write, or even more importantly, the possibility of communicating, for example, with blind people, or with children or people with reading difficulties. What’s more, it wasn’t that long ago that making a phone call was quite expensive, whereas voice messages on WhatsApp are free, as long as you have an internet connection.

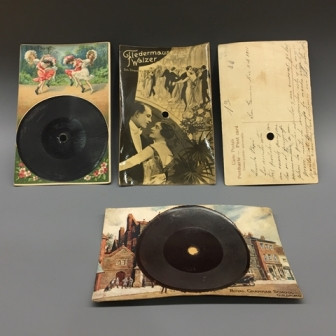

While the technologies vary, the idea has a technological precedent in a format that combines paper and vinyl (shellac), which we call gramophone postcard. We have a small and curious collection of 14 phono postcards at the Barcelona Museum of Music. They’re the typical postcard as we know them; but, at the same time, they include a small 78 rpm printed directly on a surface layer of wax or printed onto the cardboard. This record can be listened to on a normal phonograph device. That means, as we’ll see in a minute, that people sent a piece of music, taking advantage of the reverse side to write the latest news or simply send regards, news or good wishes.

The first questions come to light as we begin to dig deeper into these hybrid recordings: are they postcards or are they records? They shouldn’t be confused with the “flexidiscs”, which came about in the 1960s. They in fact were flexible vinyl sheets with the same thickness as paper, and that had more of a promotional purpose. Most of the postcards we have in the Museum are from the decades between 1910 and 1930 and, as we’ll see, these postcards were in use more or less between the years 1903 and 1980.

What should we call a postcard that contains a recording? How do we classify them or call them? We’ve found all kinds of terms according to the language used, and they all often refer to the fact that they’re hybrids or to the factory or brand. (We’ve found some of them on Mediateletipos): Carte-Disque, Carte Postale Parlante, Fonocartolino, Photo-disc, Gramophone Record Postcard, Musik-Postkarte, Phonogram card, Phonoscope, Phono postcard, Phono postcard, Phono-postal, Phonopostal, Sonorine, Singing Postcard, Sprechende Postkarte, Schallplatten-Postkarte, Talking card, Talking postcard, Tonbild-Postkarte, Vinyl postcard and so on. Here at the Museum, we call them “gramophone postcards”.

There’s an interesting titbit about the dating of the existence of this device. We find a text prior to the invention of the gramophone postcard in a novel by Jules Verne entitled, Tribulations of a Chinaman in China, published in 1879. (Verne quite often foresaw future inventions long before they came into existence, although not always, as we shall see below). There’s a scene in the book where a voice message is recorded on a paper – we’ve included the entire excerpt below:

Il s’approcha alors d’une petite table de laque, sur laquelle était posée une boîte oblongue, précieusement ciselée. Mais, au moment de l’ouvrir, sa main s’arrêta. «Que me disait sa dernière lettre?» murmura-t-il. Et, au lieu de lever le couvercle de la boîte, il poussa un ressort, fixé à l’une des extrémités. Aussitôt une voix douce de se faire entendre! «Mon petit frère aîné ! Ne suis-je plus pour vous comme la fleur Mei-houa à la première lune, comme la fleur de l’abricotier à la deuxième, comme la fleur du pêcher à la troisième ! Mon cher cœur, de pierre précieuse, à vous mille, à vous dix mille bonjours !...» C’était la voix d’une jeune femme, dont le phonographe répétait les tendres paroles. « Pauvre petite sœur cadette!» dit Kin-Fo. Puis, ouvrant la boîte, il retira de l’appareil le papier, zébré de rainures, qui venait de reproduire toutes les inflexions de la lointaine voix, et le remplace par un autre. Le phonographe était alors perfectionné à un point qu’il suffisait de parler à voix haute pour que la membrane fût impressionnée et que le rouleau, mû par un mouvement d’horlogerie, enregistrât les paroles sur le papier de l’appareil. Kin-Fo parla donc pendant une minute environ. À sa voix, toujours calme, on n’eût pu reconnaître sous quelle impression de joie ou de tristesse il formulait sa pensée. Trois ou quatre phrases, pas plus, ce fut tout ce que dit Kin-Fo. Cela fait, il suspendit le mouvement du phonographe, retira le papier spécial sur lequel l’aiguille, actionnée par la membrane, avait tracé des rainures obliques, correspondant aux paroles prononcées; puis, plaçant ce papier dans une enveloppe qu’il cacheta, il écrivit de droite à gauche l’adresse que voici.

That sums it up, an oral phonogram, printed on paper and reproducible on a phonograph. Miquel Barceló explains and summarises it by referring precisely to this excerpt, in a text on science in novels:

Or the exchange of correspondence that is established in The Tribulations of a Chinaman in China (1879) by means of discs that are played on phonographs instead of traditional letters written on paper. Not to mention the fax prototype represented by the “phonographic telegraph” of Paris in the 20th century (a work that is usually dated to around 1862, although the original was found much later in 1990, so it is possible to raise many doubts). In this case, as with the submarine, the fax was already known (at least for some) thanks to the Scottish inventor, Alexander Bain, who obtained a patent in 1843, and the modern design of the telefax is based on his original concept.”

In 1906, the Société Anonyme des Phonocartes created La Phonopostal (although there was a 1905 patent, submitted by E. J-B. Brocherioux, L.V. Marotte and P.J. Tochon, following the idea of an artist, a Mr Ambruster), to take advantage of the sending of postcards, called Sonorine, which enabled users to record voice messages on postcards as long as the recipient also had the same device to be able to listen to the message. They noticed immediately that cardboard was a fragile, easily damaged material. In 1908, the Pathé record manufacturer created the Pathépost, which opted for small, blank cardboard records, covered with black-wax, between 11 and 14 centimetres wide, which gave better results, in that they were not as fragile and sound quality was improved.

A Sonorine allowed recording up to 60 words on the flipside – the back part of the disc - and, the A side contained portraits of young women. Their brand advertising was, to say the least, eye-catching: “N’écrivez plus!” It seemed to be encouraging people to stop writing, as if it were a waste of time or an old-fashioned thing to do.

There’s another website, Obsolet Media, that states that the first time gramophones are mentioned was in 1903, when they were manufactured in Germany. And a Norwegian blog, Musikk Labler says that it wasn’t until the decade of the 1930s that production began in Norway.

In this video, Jarret New explains that gramophone postcards were especially popular in Eastern European countries such as Poland, Czechoslovakia or Hungary. It was a way to listen to music since most of what came from Western Europe was prohibited. That reminds us of how they got a hold of music in Russia: by pressing vinyls on X-rays to acquire kinds of music that couldn’t be found on the market.

However, the quality of these recordings was obviously poorer than that of a normal vinyl record, since they were made with thinner materials and were more exposed to scratches, deformations or skipping. At a later date, some companies (from Austria and California) went back to printing flexi-discs as well as gramophone postcards, with the possibility of customizing both the gramophone’s size and the format of the postcard, and letting the user choose the music that would be on it.

As a curious example of promotion, not for flexidiscs but for gramophone postcards, we find the Barça Anthem, with lyrics by Josep Badia and music by Adolf Cabané preserved in the club's museum. You can hear it here.

Let’s take a look at the sound holdings of the Museum. There are 14 gramophone postcards of various sizes and musical styles:

- Four unused Weco Tonbild-postkarten brand gramophone postcards (with nothing written on the postcard part), Germany (1929 and 1932), with the following songs: Leicher Kavallerie by Franz von Suppé, Radetzky Marsch, Fledermaus Walzer by Johann Strauss, and Krönungs-Marsch Prophet by Giacomo Meyerbeer.

- One unused, Ninophon brand postcard (nothing written on it), Munich, Germany (1950), with the song: Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht.

- Three unused Tuck's Post Card brand, England (1929-1932), with the songs, Will ye no come back again (Saxophone), Killarney and D'ye ken John Peel (Cornet).

- Two Musika brand gramophone postcards with handwritten text, Germany (1910-1911), with the songs Dollarprinzessin by Franz Lehar and Cake-Walk.

- Four Father Tuck's Musical Nursery Rhyme Record brand gramophone postcards with the songs Baa baa black sheep, Hey Diddle Diddle, Puff Puff busy train and Sing a song of sixpence.

Click on this link to see and hear them.

There is a second type, but without the postcard part. We’ve only got two of them in our collection. They’re the discs that were sent by post: they made it easier for people to record a voice message (or play an instrument, if it fit in the booth!) on a vinyl and send it. By 1920, the fashion extended throughout Europe, America and South America that took three forms: you could go to a post office to record a message and send it; record your message in a booth (at the bus or train station, tourist sites, also on boats, at fairs, and so on. All you had to do was insert a coin and you could record your voice and get a record); or buy a device for recording at home.

This same voice messaging service by post existed in Argentina. Fonopost was created in 1939. It was a service for recording a person’s voice and sending the message by regular post. Portable devices were used that recorded the message on 8-inch acetate records at 78 rpm.

Why weren’t they more successful? Because they were slow. If all you had to do was make a phone call, why send a recording that would take days to reach the recipient? (Cavallari, 2016). On the other hand, it was about converting voice itself into a souvenir. Facing a microphone (uncomfortable) or a device capable of recording sound, being aware of the possible durability and also being aware of the fact that you couldn’t edit what would be recorded. The Kodisk brand sold records for self-recording with the slogan “Snapshots of your Voice”.

This meant a change of paradigm: it went from a wax cylinder, which enabled recording and listening with the same device, to Berliner records, which started another route to marketing with more expensive devices and with more complicated technology, which were no longer available to everyone.

It may even have been a good idea to democratize recording, which at that time began to feel the preponderance of the music industry, just as happened, for example, in the photographic field: only those who had a camera could immortalize moments... start manufacturing cheaper machines or booths which made taking pictures available to everyone, or at least a possible option.

In the 1960s there was a second wave that brought gramophone postcards back into fashion, but it was a marginal or small-time production that even went unnoticed to ordinary postcard collectors. The best-known brands of that decade were: Discoflex, Mexisonor, Punch, Photochrom, Musicarte and SECITEM.

We’ve found two witnesses from that decade who have told us about a booth where people could record their voice. It was below Plaça Catalunya. One of them, Jordi Codina, strapped on a guitar to record two carols and, the other, recorded a children's song in French. Both people had the same objective: to make a gift. Therefore, they avoided everything that had already been done, and seemed too industrially produced. Instead they chose to customize their own voices.

In the case of records sent by post, there is a project at Princeton University in which Professor Levin has collected nearly 2000 recordings, which he has photographed, described and digitized, and that can be freely accessed at this link: https://www.phono-post.org/browse.cgi

In short, we have two very different types: the gramophone postcard, understood as a publication in shellacked cardboard format, with pre-defined music chosen by the industry. They were sent as a cool fashionable sort of thing. (This brings to mind the birthday cards that sound when opened and there are still chips sold to record messages and include them, precisely, in cards.) The second are self-recorded records sent by post, which implies the technological and economic possibility of deciding what to record, what message or song to add, whether it was for home use as a memento, or to give as a gift, because you could customize the content without having to resort to professional recording studios.

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR MORE IN-DEPTH STUDY

CAVALLARI, Peppe. (2016). Cahir Louis Lumiére Nº 10. Le phonopostale et les sonorines: un échec riche d’idées. At <https://www.ens-louis-lumiere.fr/sites/default/files/2018-06/cahierlouislumiere10.pdf> [Last checked: 15 May 2019]

LOMOTZ, Mirco. (2015). Vimeo. Phono-Post : A Media Archaeology of Voice Mail. At <https://vimeo.com/119368640> [Last checked: 16 May 2019]

LOTZ, Rainer E. Lotz Verlag. Phonocard and Phonopòst History. At <http://www.lotz-verlag.de/Online-Disco-Phonocards.html> [Last checked: 15 May 2019]

Phonopost case study. At <https://www.data-futures.org/phono-post.html> [Last checked: 15 May 2019]