#Trànsits 2023-2024 (summary of the spring sessions)

The Museu de la Música de Barcelona and the Office of Religious Affairs (OAR) are organising the second edition of the ‘Trànsits: les músiques de l’esperit’ [Transitions: Music of the Spirit] programme as part of L’Auditori’s ‘Poder o revolta’ [Power or Revolt] season. This new edition began in the autumn of last year, and concluded this spring. During the months of April and May, the following sessions took place: “Shawn Mativetsky: Music from North India”, “Cuncordu Codronzanesu: Traditional Sardinian Polyphonic Singing” and “Orthodox Easter: Music of the Romanian Orthodox Church”. All of them kept to the dual format used previously, consisting of a discussion with experts or members of the communities focused on in each session, and a spiritual or religious musical practice.

Music and spirituality have always been closely linked, across different eras and within different contexts and human groups. For many religions and spiritualities, sound has been the basis for both individual and collective encounters with divinity and transcendence. The cross-cutting nature of these practices allows for the establishment of links between very different cultures in such a way that music becomes a key meeting point for diverse communities.

As part of the second edition of the “Poder o revolta” [Power or Revolt] season at L’Auditori, the “Trànsits: músiques de l’esperit” [Transits: Music of the Spirit] programme, organised by the Museu de la Música de Barcelona and the Office of Religious Affairs (OAR), has sought to reflect this reality through the dissemination and celebration of religious and spiritual practices involving music in a series of sessions in which “the religions and spiritualities of different communities in the city with a shared musical component make dialogue and understanding possible, not just between individuals, but between groups with established dynamics, shared practices, calendars and social norms”, said Jordi Alomar, director of the Museu de la Música in an interview for the OAR’s blog.

Each of the activities and sessions was centred on showcasing a religious or spiritual practice where music and sound play a leading role, complemented by a discussion with experts or members of the community. The spring season included three sessions during the months of April and May: “Shawn Mativetsky: Music from North India”, “Cuncordu Codronzanesu: Traditional Sardinian Polyphonic Singing”, and “Orthodox Easter: Music of the Romanian Orthodox Church”.

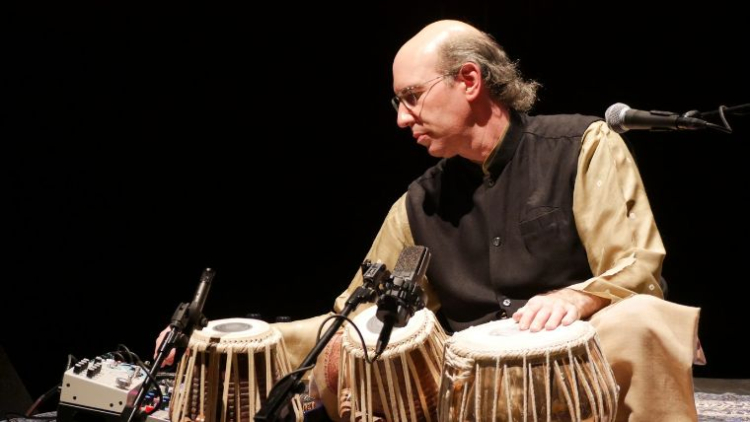

SHAWN MATIVETSKY. MUSIC FROM NORTH INDIA

On 19 April, Shawn Mativetsky gave a tabla performance in the Sala Alicia de Larrocha at L’Auditori, devoted to highlighting the link between music and spirituality within Indian culture. The session began with an introductory conversation between Shyam Sunder, a sitar and bansuri player from New Delhi, and Vignesh Melwani, a performing artist and cultural activist from Barcelona, who released the experimental album Improvisuals in 2023. It was moderated by Horacio Curti, ethnomusicologist, professor, and coordinator of the Asian music programme at the ESMUC. The speakers explored in depth the significance of music in Indian culture, noting the strong spiritual component of the country’s sound universe.

Shyam Sunder began by explaining that music in India implies a strong sense of transcendence, rooted in both theory and practice: “To make music you have to start with sound, which is a seed that given certain conditions can grow like a flower, plant or tree – and become music. And the musicians need to be able to sing each sound before they play it”. Vignesh Melwani corroborated this and also explained that this practice is repeated in the performing arts in India: “In the thousand-year-old Indian treatise on the performing arts, Natya Shastra, there is a story of someone who wanted to learn to act. He is told that if he wants to learn to act, he must first learn to dance. If you want to learn to dance, you must first know how to play an instrument. And if you want to play an instrument, you have to know how to sing.”

This way of understanding music is very different to the one that dominates in the West. It is this concept of practice that makes Indian music a vehicle for catharsis. “Indian music and aesthetics have a very strong spiritual base”, said Melwani, “the only thing I’ve found equal to that base is the Gypsy ‘duende’, or perhaps the spirituality that 20th century Russian artists such as Kandinsky were drawing from”. He went on to say that “it’s a process of seeking a very pure essence”.

Sunder observed that the tabla is “indispensable, it’s two of the four wheels of the car that is Indian music”. It is a pair of drums, a wooden membranophone and a clay drum, with a huge range of sonorities. For this reason, it is referred to as a “tuned percussion instrument”, explained Horacio Curti, “which means that despite being a percussion instrument, it allows you to play different melodies, with both high and low-pitched sounds”. The conversation was followed by a musical performance by Shawn Mativetsky, who drew on his extensive experience and the teachings of his mentor, soloist Pandit Sharda Sahi, to give the audience a multi-faceted overview of the instrument, with traditional solos in the Benares gharana style, developed over two hundred years ago by Pandit Ram Sahai (1780-1826), as well as new, more experimental compositions. The concert repertoire included the works Tabla Solo in Teental, Generation Recall (2023), Everything is Broken (2023), Starfield (2024) and Tabla Solo in Rupaktaal.

View the gallery of images from the “Shawn Mativetsky: Music of North India” activity here.

Watch the video of the dialogue here and the one of the performance here.

CUNCORDU CODRONZANESU, TRADITIONAL SARDINIAN POLYPHONIC SINGING

While the April session focused on the intrinsic spirituality of the world of Indian music, the “Cuncordu Codronzanesu: Traditional Sardinian Polyphonic Singing” activity highlighted the quest for divinity through the practice of liturgical polyphonic singing in Sardinian Catholic Christianity. This activity took place over two sessions at different venues.

There was a preliminary discussion about this practice, and a small musical performance at the Tradicionàrius Crafts Centre on 10 May. Taking part in the conversation, which focused on the distinctive features of the a cuncordu songs and their spiritual significance, were Lugiano Cossu (maestro and tenor) and Luigi Betza (baritone) from the Su Cuncordu Codronzanesu group, and Maria Antonietta Muggianu, a singer of Sardinian origin who specialises in early music based on historically documented interpretations. The moderator was Ester Llop, a teacher of music and ethnomusicologist specialising in oral music and the Cant dels Goigs [‘Els Goigs’ are poetic compositions generally sung in praise of a saint or virgin in the Catholic church].

The session aimed to explain the specific features of a cuncordu singing, an a cappella musical practice from the island of Sardinia very closely linked to the Catholic faith, that goes hand in hand with various liturgical and paraliturgical practices, or is found in the form of compositions for Masses with special meanings. “Cuncordu means harmony. In the musical sense, yes, but also within the heart, because without harmony in your heart you can’t sing a cuncordu,” explained Luigi Betza.

Harmony is fundamental for polyphonic singing like this, where the four male voices (a tenor, a leggero tenor, a baritone and a bass), “always go together, in the same melodic line”, said Lugiano Cossu. In fact, added Maria Antonietta Muggianu, a cuncordu singing “is carefully thought out – intonation, volume and harmony are all meticulously controlled. Furthermore, the singers use non-verbal means of communication, because there’s no score, and you have to strike a balance at all times”. That is why one of the distinctive features is that “it’s never exactly the same. If we sing a song ten times, it’ll be different each and every time”.

In fact, a cuncordu singing has always been transmitted orally, from its origins back in the 12th century as a Christian appropriation of ‘tenor profà sard’ singing, right up to the present day. “It’s an expression of the Sardinians’ strong sense of identity, of a culture that has survived over time despite being passed on orally, with all the speculation and randomness in terms of its evolution that this may entail”, said Muggianu. This means that a cuncordu singing has reached the present day with variations, which are also the result of a marked regionalism. It even disappeared completely in some places in Sardinia between the 1960s and the 1990s, but more recently it has been revived by groups like Su Cuncordu Codronzanesu.

Since 2009, the ensemble has been working on rebuilding the repertoire of the Arciconfraternità de Santa Croce de Rosario, a former ensemble from the town of Codronzanesu, where the four members of the group come from. They are one example of the “generational renewal” of the practice that Muggianu commented on. Because, says Betza, “losing our tradition would have been a sin”. For him the challenge was “not simply to revive this form of singing as such, but also the Christian culture and traditions with secular roots surrounding it as well.

Su Cuncordu Codronzanesu were invited to perform at both sessions in this part of the “Trànsits” programme. At the first, on 10 May, the ensemble brought the event to a close with a concert featuring a repertoire of a more secular nature. The following day, Su Cuncordu Codronzanesu gave a full liturgical concert in the crypt at the Sagrada Família.

View the gallery of images from the “Cuncordu Codronzanesu: Traditional Sardinian Polyphonic Singing” here.

The videos of the discussion and performance will soon be available on the OAR’s blog.

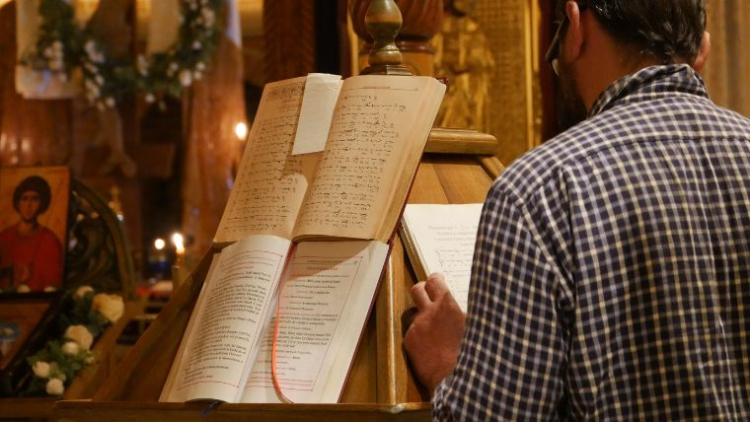

ORTHODOX EASTER. THE MUSIC OF THE ROMANIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH

The last session of the second edition of the “Trànsits” programme focused on Romanian Orthodox Easter and its liturgical sound practices. Like the previous event, it took place over two different days. The discussion was on 16 May, at the Museu de la Música, and the mass, which was open to the public, was held on 18 May at the parish church of Sant Jordi (Patriarchate of Romania), one of the fourteen Romanian Orthodox churches in Catalonia and the only one in Barcelona.

A discussion between Father Stefan-Silvan Vintu Bunda, priest at the Church of Sant Jordi (Patriarchate of Romania), Jordi Sacasas Segura, archivist and curator at the Basílica de Santa Maria del Pi in Barcelona, and Alejandro Mateo García, a graduate of the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya (ESMUC) in historical violin and musicologist in training, who was baptised in the Romanian Orthodox Christian tradition and has an interest in Byzantine chant and its use in Orthodox spirituality. Bezawerk Oliver Martínez, who is responsible for contact with Christian communities at the Office of Religious Affairs, acted as moderator.

The session highlighted the importance of music in Orthodox liturgical practices, a legacy of Byzantine mysticism in which music and song served as a vehicle for worship, and for the transmission of spirituality and transcendence. The discussion opened with a contextualisation of the structure of the Orthodox liturgy and the role of Byzantine chant and musicology by Alejandro Mateo García. The musicologist explained that the Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom – which could be observed at the mass on Saturday 18 May – has four parts: the prelude, where prayers are said for the well-being and guidance of God; the celebration of the Word, where the faithful are made ready to listen to the sacred scripture; the reading of the day, delivered by the priest; and the celebration of the Eucharist. In each of the parts, it is the sound of the voice that is of primary importance, and it can take three different forms: monophonic singing, the intoned word, or the spoken word.

For Mateo, the latter has significant benefits: “When the liturgy in its entirety is sung, the voice is projected to a much greater degree, and the musical textures developed using the Byzantine technique favour the understanding of the text, fixing the words in the mind and in the spirit, and facilitating the assimilation of the liturgical message”. This differentiates Byzantine or Orthodox music from Catholic music, where there is a preference for polyphony, which, according to the speaker, “ends up watering down the message”.

Following Mateo’s presentation of the context, he and the other speakers reflected on and discussed a number of issues related to the close ties between music and the religious practices of the Romanian churches. Here Vintu echoed Mateo’s remarks, underlining the all-important role of melody in Orthodox liturgies: “The melodic line is the soul that stirs the body, which is the text. To find God we need look within, to our souls; and the soul emerges through the music”.

Sacasas talked about this tendency in Catholic musical liturgical practices, saying that he felt that they had abandoned the idea that music is something more than an aesthetic experience, and can be a conduit to the divine: “You don’t come to God through reflection, but through sensitivity. Whether through painting or music, all religious traditions understand that faith is an emotional experience, a feeling. Vintu noted that this inclination towards aesthetic experience has been kept alive, and is reflected in the practices that Orthodox tradition still follows in its liturgies today. Because “the Orthodox Church has a tradition of avoiding change, of keeping things as they are – in the process of adaptation, some thongs are lost”.

Those attending the liturgical service open to the public on the morning of Saturday 18 May were able to experience these things for themselves in the celebration of Orthodox Easter, which, as was the case this year, often takes place on a different week to Catholic Easter, as it is governed by the Julian calendar.

View the gallery of images from the “Orthodox Easter” activity here.

The videos of the discussion and the mass will soon be available on the OAR’s blog.